Delphi continues to power important systems in finance, manufacturing, healthcare, logistics, and the public sector. Many of these applications are ten, fifteen, or even twenty years old, yet they still handle essential work: processing transactions, enforcing business rules, producing reports, and keeping daily operations running. Because Embarcadero actively maintains Delphi and provides upgrade tools, keeping these systems in place is often a reasonable choice.

For technology leaders in 2026, the issue is rarely system functionality, but alignment with current business needs. As organizations grow, friction tends to increase: release cycles slow, integrations require more effort, and security reviews take longer. Individually, these challenges may seem manageable, yet over time, they accumulate and signal that the system may no longer support growth as effectively as before.

In this article, we examine why many organizations continue supporting Delphi and which business signals suggest it may be time to reassess that decision. We also outline what migration looks like in practice and how teams approach it as a staged, risk-managed investment.

When migration becomes a strategic consideration: 7 key signals

Delphi development solutions often remain technically sound long after the business environment around them has changed. In a previous article, we explored why stability, predictable costs, and low regression risk still justify continued Delphi support in many cases.

What usually shifts first is not correctness, but adaptability. The application continues to run, data remains accurate, and users can complete their tasks. Over time, however, the effort required to change the system increases. Simple modifications take longer, coordination becomes harder, and risk tolerance narrows.

Migration decisions are rarely driven by a single issue. They typically emerge when several challenges appear at the same time, even if not all at once. Each may be manageable on its own, but together they often signal that the system no longer aligns with current business requirements. Below are a few examples.

1. Active product development becomes a constraint

When a product must continue evolving, development speed becomes a business variable rather than a technical one. Teams often notice that routine changes require disproportionate effort.

This usually shows up as:

- Longer lead times for even modest feature requests

- Increased hesitation around touching certain modules

- A growing gap between planned and actual delivery dates

The issue is not that change is impossible, but that it is expensive in time, coordination, and risk. Over time, this affects competitiveness and internal innovation.

2. Access expectations change faster than desktop-first systems can adapt

Many long-lived Delphi applications were designed around assumptions that made sense at the time: users worked on managed desktops, access was local or VPN-based, and interaction patterns were tightly coupled to Windows UI frameworks. As organizations adopt cloud platforms, hybrid work models, and mobile access, those assumptions start to create friction.

Teams often try to bridge the gap with tactical solutions. These approaches can be effective in the short term, but they tend to introduce new risks and operational overhead as usage expands.

As access patterns shift, the underlying issue is rarely about adopting a specific technology for its own sake. The pressure comes from misalignment between how people need to work and how the system was originally structured.

At this point, migration discussions usually focus on restoring alignment by separating access concerns from core business logic, so that web, cloud, or mobile interfaces can evolve without continuously stretching a desktop-centric architecture beyond its limits.

3. Integration pressure increases steadily

Modern enterprise systems are expected to exchange data continuously with other platforms. Payment providers, ERP systems, BI tools, partner portals, and internal services all rely on stable interfaces, predictable data contracts, and well-defined failure handling.

As this ecosystem grows, integration stops being an occasional task and becomes an ongoing operational concern. In Delphi-based environments, integration pressure often shows up indirectly, through patterns such as:

- One-off scripts or manual export/import routines created to satisfy a specific partner or reporting request

- Direct database access by external tools because no formal API exists

- Tight coupling between integration logic and core application code, making even small changes risky

- Reluctance to add new integrations because of uncertainty around side effects on existing workflows

A common example is a Delphi desktop application that originally exported CSV files for monthly reporting. As the business grows, those exports are consumed by multiple downstream systems: a data warehouse, a compliance reporting tool, and an external partner.

Each consumer introduces slightly different requirements, leading to custom scripts, conditional logic, and manual steps. Over time, the export process becomes critical infrastructure, yet remains fragile and poorly isolated from the core system.

4. Security and compliance efforts grow disproportionately

Security expectations evolve independently of application functionality. Identity models, encryption standards, logging requirements, and audit expectations change over time.

Operationally, this often looks like:

- Security reviews take longer with each release

- Additional controls wrapped around the system rather than built into it

- Increasing effort to produce audit evidence

The application may still behave correctly, but the surrounding ecosystem no longer aligns cleanly with modern security and compliance baselines.

5. Support and maintenance costs trend upward

Even when a Delphi system remains functionally stable, the cost of keeping it stable tends to rise over time. These increases are rarely obvious in a single line item. They usually emerge gradually across staffing, tooling, and operational overhead.

What makes this challenging is that the application itself may not be changing much, while the environment around it does. Operating systems evolve, databases are upgraded, security policies tighten, and expectations around reliability increase. Each of these shifts adds incremental effort to routine maintenance.

When maintenance absorbs a growing share of engineering capacity, organizations start questioning whether continued support still represents the lowest total cost of ownership.

6. Knowledge concentration creates fragility

A common risk pattern in long-lived systems is extreme knowledge concentration. Often referred to as a bus factor, this describes how many people could leave before the system becomes difficult to operate or change.

Concrete examples include:

- One person who understands critical data flows or edge cases

- Architectural decisions that exist only in someone’s memory

- Areas of the codebase that are avoided because their impact is unclear

This risk tends to remain invisible until availability changes force the issue. Migration discussions frequently begin as a response to this fragility rather than to technical dissatisfaction.

7. Incidents and recovery effort increase

Finally, operational signals matter even when outages are rare. Slow recovery or high manual effort often indicates deeper structural issues.

At this point, the system’s stability becomes an operational and organizational risk, prompting a reassessment of long-term viability.

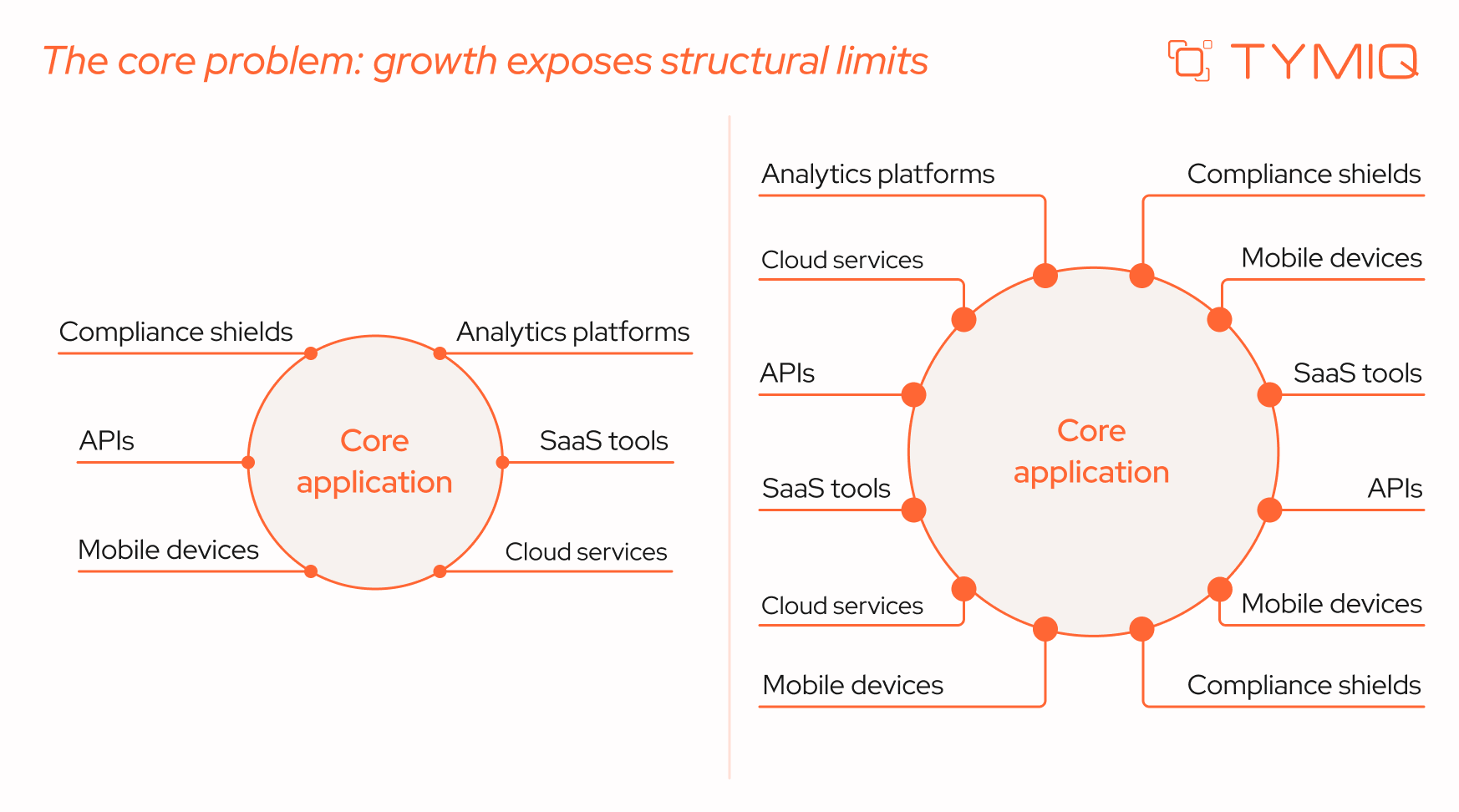

The core problem: growth exposes structural limits

Most Delphi systems were designed during a different phase of the business lifecycle. At the time they were built, assumptions were reasonable:

- Teams were smaller and more centralized

- Integrations were limited and often batch-based

- Desktop applications matched user expectations

- Regulatory and security requirements were simpler

As organizations evolve, these assumptions change. Delivery cycles shorten as competition increases. Customers and partners expect near-real-time data exchange. Internal teams expect web access, remote workflows, and modern user interfaces. Security and compliance expectations tighten as data volumes and exposure increase.

Importantly, these changes do not make the existing system “bad.” In many cases, the system continues to perform its original function reliably. The issue is that the surrounding environment changes faster than the system was designed to adapt.

At this stage, the system often slows down development and decision-making. Changes take longer. Integrations require workarounds. Operational risk increases incrementally. None of these mandates migration on its own, but it does justify a closer look at long-term sustainability.

When migration becomes a rational business choice

1. The product must remain under active development

When new features are central to business growth (whether to meet customer demand, regulatory change, or competitive pressure), delivery speed matters. If each change takes significantly longer than expected due to architectural constraints, release bottlenecks become a strategic issue.

Over time, teams may compensate by reducing scope, delaying improvements, or adding manual processes. These responses mask the underlying constraint but do not remove it.

2. Web, cloud, or mobile capabilities are required

Many Delphi systems were designed as desktop-first applications operating within controlled internal networks. When access expands to cloud environments, hybrid work models, or mobile usage, teams often introduce remote desktop layers, VPN gateways, or thin web wrappers to extend availability.

These measures can keep the system usable, but they gradually introduce architectural strain:

- Extra infrastructure to maintain and monitor (RDP hosts, gateways, session brokers)

- Broader security exposure and more complex configuration management

- Limited scalability compared to service-based architectures

- User experience constraints that do not align with browser or mobile standards

Over time, the gap between how users need to access the system and how the system was originally designed to operate becomes harder to bridge.

3. Integration with modern APIs becomes unavoidable

Modern business ecosystems depend on APIs, event streams, and service-to-service communication. Partners, SaaS tools, and analytics platforms assume these interfaces exist.

Systems that cannot expose services cleanly – or that rely on brittle integration mechanisms – become bottlenecks. Integration work that should be routine turns into custom engineering, increasing cost and risk.

4. Security and compliance requirements intensify

Security expectations evolve independently of application age. Frameworks such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework formalize requirements around monitoring, incident response, and auditability. OWASP guidance for legacy applications highlights that while compensating controls can reduce risk, structural change is often necessary to meet modern baselines.

Platform lifecycle changes can also force action. Microsoft’s deprecation of Basic Authentication in Exchange Online is one example of how external changes can break legacy integrations if systems are not updated.

5. Support and maintenance costs rise steadily

Over time, maintenance costs often increase even when functionality remains stable. Specialized skills command higher rates. Older tooling requires care. Compatibility issues with operating systems, databases, and security tools accumulate.

Over time, maintenance work can crowd out new development, even if the total headcount remains unchanged.

What migration actually involves

A common misconception is that migration requires replacing everything at once. In practice, successful initiatives treat migration as a sequence of controlled changes, each with its own risk profile.

What teams migrate in practice

Across real projects – including those we have implemented – this pattern is common. Core business logic is preserved initially while user interfaces are modernized. Reporting and integration layers are addressed early to satisfy compliance or partner requirements. Complex calculation engines are deferred until boundaries and test coverage are adequate.

Three proven migration strategies

There is no universal migration strategy. The appropriate approach depends on system criticality, timelines, and tolerance for operational risk.

1.Big Bang migration

Simply put, the entire system is replaced in a single cutover.

Why choose this approach? It is typically selected when leadership wants a clean architectural break without maintaining parallel systems. It can reduce the duration of dual maintenance, avoid prolonged coexistence complexity, and deliver a fully modernized environment faster – assuming requirements are stable and well understood.

This strategy can work for smaller applications with limited dependencies and well-documented requirements. Its primary risk is concentration: if assumptions are wrong, recovery is expensive and slow.

2.Strangler (incremental replacement)

New components are introduced alongside the legacy system and gradually assume responsibility.

This approach allows teams to deliver value incrementally, learn from real usage, and adjust scope over time. It requires careful boundary management but offers strong risk control.

3.Hybrid approach

Some components are retained while others are replaced. This is common when certain logic is risky to rewrite or when timelines and budgets are constrained. The trade-off is temporary complexity, which must be actively governed.

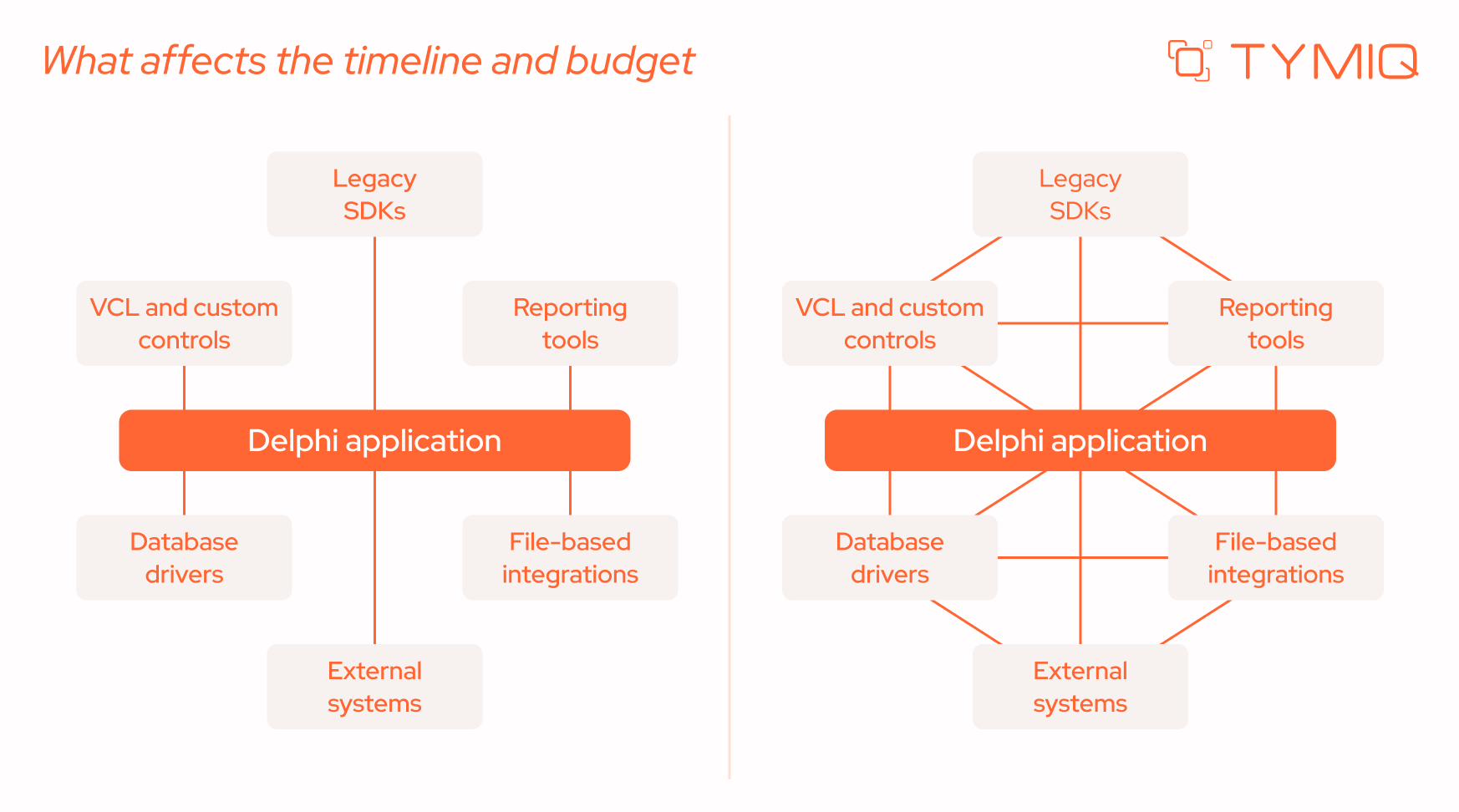

What affects the timeline and budget

Migration effort is driven less by the size of a Delphi system and more by how it is structured and what it depends on. Two applications with a similar number of lines of code can require very different levels of effort depending on architectural decisions made years ago and the way the system has evolved since.

In practice, timelines and budgets are shaped by a small number of technical factors that influence how safely and incrementally the system can be changed.

These factors explain why migration estimates based only on application size or age are often misleading. Systems built incrementally, with some separation between UI, logic, and data, tend to migrate faster, even if they are large. Systems that grew organically without clear boundaries usually require more preparatory work.

Stabilization: what you can do without migrating

Migration is not always the first or immediate step. Stabilization reduces risk and creates optionality.

A structured stabilization effort typically moves through identifiable milestones. Teams first achieve visibility into system boundaries and dependencies, then establish reproducible builds and basic test coverage, and finally reduce the most critical sources of technical fragility. It’s important to note that reaching these milestones does not modernize the architecture, but it significantly improves control over it.

Below is a practical stabilization checklist from TYMIQ experts that teams can use to track progress.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

TYMIQ experts often say that migration projects rarely fail because of technology choices. They fail because uncertainty is underestimated at the beginning. Below are the most common pitfalls we see in practice – and how to avoid them.

Rewriting without clear requirements

When legacy behavior is not explicitly documented, teams unintentionally redesign parts of the system while trying to “clean things up.” New interpretations of workflows emerge mid-project, expanding scope and timelines.

Mitigation tip: Before writing new code, document current business rules and edge cases with stakeholders, especially in finance, reporting, and integration-heavy modules.

Overreliance on automation

Conversion tools can accelerate syntax translation, but they cannot reconstruct undocumented assumptions, data quirks, or domain-specific edge cases embedded in years of usage. Automated output often compiles, yet still requires architectural correction.

Mitigation tip: Treat automated conversion as a starting baseline and allocate time for structured code review and domain validation by experienced engineers.

Skipping tests and discovery

Without baseline tests and system analysis, teams cannot objectively confirm that migrated functionality behaves as expected. Problems surface late and are harder to isolate.

Mitigation tip: Establish smoke tests and identify high-risk workflows before major refactoring begins, even if full coverage is not immediately feasible.

How the TYMIQ team de-risks migration in practice

Across successful initiatives, a consistent sequence tends to produce the most predictable results:

Each stage has a specific purpose and tangible outputs.

1. Discovery phase

The Discovery phase (typically 2-6 weeks) serves as a structured learning platform. It provides clarity before major investment decisions are made.

It should include:

- Codebase structure analysis and complexity review

- Dependency and third-party component mapping

- Database schema and data flow assessment

- Security and compliance gap identification

- Comparison of multiple scenarios (continue, stabilize, migrate) with effort ranges

2. Roadmap

The roadmap translates findings into a practical execution model. It defines:

- Target architecture and platform choices

- Migration boundaries and sequencing

- Integration strategy (APIs, services, adapters)

- Risk mitigation steps and rollback options

- Budget phases aligned with deliverables

This stage prevents migration from becoming an open-ended modernization effort without measurable checkpoints.

3. Pilot

A pilot validates assumptions in a controlled environment. Teams typically select:

- A non-critical module

- A reporting component

- Or a bounded integration layer

The goal is to test tooling, workflows, performance characteristics, and collaboration patterns before scaling further.

4. Phased migration

After validation, migration proceeds in controlled increments. Common sequencing patterns include:

- UI modernization first

- Integration and reporting extraction

- Gradual replatforming of core services

- Data domain separation and staged cutovers

Each increment should have defined acceptance criteria and measurable business outcomes. Parallel operation periods must include clear exit criteria to avoid long-term dual-system overhead.

This staged model transforms migration into a managed investment with feedback loops, controlled exposure, and measurable progress.

Closing perspective

Delphi’s age alone does not make it a problem. Many systems continue to deliver real business value. Risk emerges when business direction, security expectations, talent availability, and operational resilience drift out of alignment with what the system can support.

Migration, when it becomes necessary, is not about rewriting everything. It is about restoring control through deliberate, staged change based on evidence rather than urgency.

.webp)

.png)

.svg)