Cloud-native ETL has become the de facto standard for organizations prioritizing rapid analytics and operational efficiency. However, “serverless” and “warehouse-first” are not silver bullets: they change where you bear complexity (compute, storage, or governance), and that tradeoff matters for scale, cost, and compliance.

This guide provides concrete architecture patterns and decision criteria to help you choose the right mix of ETL, ELT, serverless, and managed compute.

When should you adopt serverless? When should you reserve dedicated compute? How do you evaluate tools for TB-scale pipelines without introducing new technical debt? By the end of this guide, you’ll have clear answers and a decision framework you can apply immediately.

How do cloud, cloud-native, and cloud-enabled architectures differ – and which should you use?

Any good guide starts with the basics, and this one is no different. Modern enterprises need a solid grasp of how these technologies differ – and for good reason. Cloud-native applications are built to “grow” in the cloud, which means they can be changed quickly, even frequently, without disrupting their functionality or the services that depend on them.

Although cloud, cloud-native, and cloud-enabled terms sound similar, they describe very different concepts: a location, a design philosophy, and a legacy adaptation pattern. Here’s a clearer breakdown.

1. Cloud

In its simplest form, cloud refers to where applications, databases, or servers reside. Instead of running locally on a physical machine, resources are hosted remotely and accessed via the internet – typically through a browser or API. SaaS tools are classic examples: the software lives in the cloud, not on your device.

2. Cloud-native

Cloud-native architecture is a design model built for elastic scaling and automated operations using containers, microservices, and API-driven infrastructure. It describes how applications are designed, deployed, and managed, not where they run.

One of the earliest pioneers of this model was Netflix. The company realized that running a global streaming platform didn’t require owning infrastructure, so it went “all in” on the public cloud.

Over time, Netflix built one of the world’s largest cloud-native applications. In hindsight, AWS played a major role in enabling this growth: rapid, elastic scaling combined with globally consistent APIs allowed the same codebase to be deployed worldwide with minimal changes – drastically reducing time and operational cost.

Crucially, cloud-native systems don’t need to physically reside in the cloud. They can be deployed on-premises using Kubernetes or other orchestrators, showing that cloud-native is a methodology, not a hosting model. Some cloud-native platforms even offer on-premises, license-based versions, the opposite of pure SaaS.

3. Cloud-enabled

Cloud-enabled applications are legacy systems originally built with monolithic or traditional patterns, then later adapted for cloud hosting. They often run in VMs or wrapped containers but still retain legacy constraints.

A cloud-enabled application is like a 30-year-old house retrofitted with solar panels. The exterior stays the same, but it’s been upgraded just enough to benefit from newer infrastructure. It works – but it doesn’t become a modern smart home.

Ultimately, cloud-native systems favor modular, scalable compute; cloud-enabled ones often inherit legacy constraints; and pure cloud hosting simply provides the execution environment.

These architectural choices directly influence whether transformations should happen before loading (ETL) or after loading into a warehouse or lakehouse (ELT), and they shape which patterns are feasible, performant, or compliant in a given environment.

ETL vs. ELT in the cloud

Before choosing tools or architectures, you need to be clear about where transformations should live. In cloud environments, that decision matters more than it used to: compute and storage scale independently, SQL engines have become extremely powerful, and governance requirements dictate where sensitive logic can legally run.

Cloud separates durable storage from compute. That separation is the reason ELT became practical: load raw data to a scalable warehouse or lakehouse, then transform using that platform’s compute and optimizers.

ELT is great when transformations are set-based SQL, idempotent, and benefit from pushdown and query engines. It reduces operational surface area, accelerates analyst velocity, and simplifies lineage when the warehouse/catalog integrates tightly with transformation tooling.

ETL still has a role. If transformations require complex Python/Scala/Java logic, ML preprocessing, or must run before data lands for masking/compliance, ETL gives the control you need. ETL fits better when you must validate or strip sensitive fields before any storage, or when multi-step, iterative logic is awkward to express or expensive inside the warehouse.

In many organizations, the best approach to data integration is hybrid: using lightweight ETL for cleansing and governance, and ELT for analytics modeling.

To understand which pattern actually fits your workload, you also need to understand the execution models that run these pipelines. Cloud-native ETL can operate on two fundamentally different compute models – server-based and serverless – and your choice heavily influences performance, cost, and governance outcomes.

Server-based (provisioned/dedicated compute)

This model uses persistent clusters or VMs with fixed compute capacity. Examples include EMR clusters, Dataproc clusters, self-managed Spark, or long-running Kubernetes workloads. You choose the node types, memory, CPU, and scaling rules — and you pay for the infrastructure while it runs, whether cloud data pipelines are idle or busy.

This model is predictable, tunable, and stable, which makes it ideal for long-running jobs, wide joins, iterative algorithms, and workloads that require fine-grained JVM, memory, or network tuning.

Serverless (fully managed, on-demand compute)

Serverless ETL removes the need to manage infrastructure. Jobs run on ephemeral compute, auto-scaled by the provider, and billed per invocation or per second. Examples include: AWS Glue Serverless, BigQuery Dataflow runner, Databricks Serverless, Azure Synapse Serverless Spark.

The runtime is provisioned just-in-time, scales automatically, and shuts down when the job finishes. This is ideal for spiky workloads, micro-batches, ingestion tasks, and pipelines composed of short, parallelizable operations.

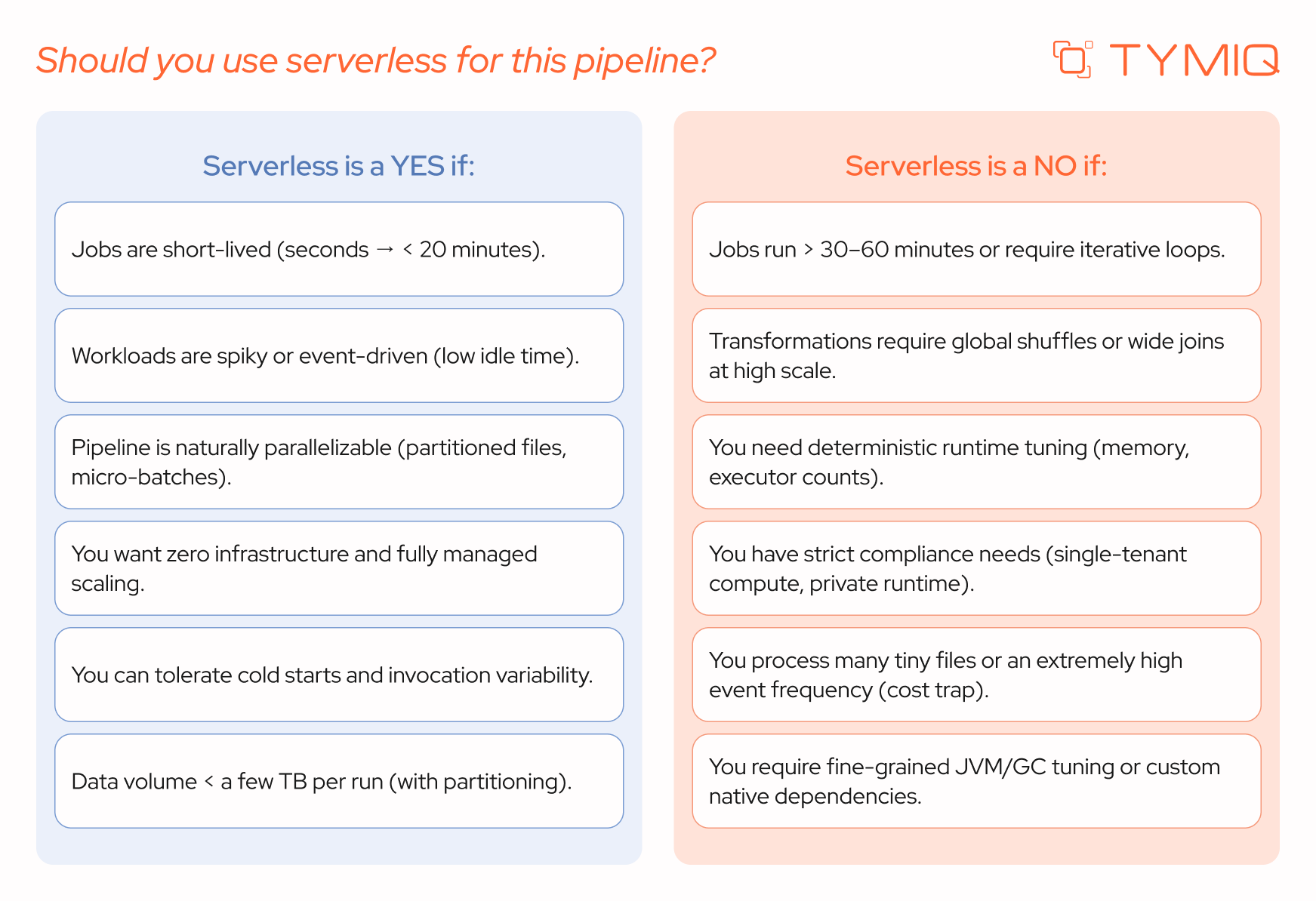

Serverless frameworks simplify big data ETL pipelines but work best for short-lived, parallelizable jobs. It is not suitable for multi-hour transformations, jobs requiring precise JVM/memory tuning, or heavy stateful operations. Long-running jobs and iterative algorithms run more predictably on dedicated clusters where executor memory, network locality, and GC behavior can be tuned.

If in doubt, here is a short list of markers that can help you get it right.

How serverless ETL costs compare to traditional pipelines

Serverless costs scale with consumption events – each invocation, each second of compute, and each interaction with storage, catalogs, or metadata services. This makes serverless highly cost-efficient for bursty, low-duty-cycle, or event-driven pipelines where traditional clusters would sit idle.

However, terabyte-scale (TB+) workloads change the equation. TB-scale refers to pipelines processing trillions of bytes – large fact tables, multi-year logs, event streams, or raw data lakes. At this scale, architecture choices have an outsized impact: the wrong pattern can multiply costs, stretch runtimes into hours, or overwhelm metadata systems.

Serverless struggles when pipelines involve thousands of tiny partitions, cross-region reads, or high metadata churn – all of which trigger excessive per-invocation overhead. And long-running transformations begin to accumulate cost faster than on provisioned clusters or warehouse ELT engines optimized for large scans.

Let’s break down how the two cost models differ in practice.

Can serverless handle big data (TB+ Workloads)?

Short answer: yes – serverless can handle TB-scale workloads, if designed properly.

Serverless runtimes scale horizontally across hundreds of workers, but only if the data is partitioned well. Columnar formats and table metadata pruning matter more than raw compute, especially at TB scale.

Partitioning, parallelism, and columnar formats (Parquet/ORC) let serverless engines prune unnecessary data and skip expensive work. Table formats like Delta, Iceberg, and Hudi further optimize read paths and metadata operations.

Serverless performs best when transformations are map-heavy (filters, projections, light enrichment) and data is columnar, partitioned, and optimized.

TB-scale anti-patterns include:

- Very wide joins with high-cardinality keys

- Serial ingestion that forces full-file scans

- “Small file explosion” that inflates metadata and invocation overhead

For pipelines requiring large shuffles, iterative algorithms, or repeated heavy joins, a managed Spark cluster or a warehouse with strong pushdown is usually more predictable and cost-efficient.

Top tools for cloud-native ETL

Serverless engines, warehouse ELT platforms, and streaming systems each optimize for different parts of the workload spectrum – and choosing the wrong tool can turn TB-scale transformations from “fast and cheap” into “slow and expensive.” With the architectural patterns now clear, we can map them to the tools that execute them effectively in real cloud environments.

Best tools for cloud-native ETL include:

- Warehouse-first ELT (SQL-heavy workloads): Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift.

- Serverless Spark: AWS Glue, Databricks Serverless, Dataproc Serverless.

- Streaming enrichment: Apache Beam/Dataflow, Kafka Streams, Kinesis Data Analytics.

- Orchestration: Airflow (MWAA), Dagster, Prefect.

More often, a successful ETL modernization goes beyond picking the right tools – it requires careful assessment of legacy data integration logic, staged migration, and robust operational oversight. For example, in one recent project, TYMIQ helped an air traffic control company maintain and modernize its legacy ATC-IDS system while migrating it from .NET Framework to .NET Core.

By running the old system alongside modernization, the team reduced risks and built a resilient, future-ready platform. It shows that even the best tools can’t fix weak architecture or missing processes.

That’s why we rely on our own set of principles that guide every design choice – guiding teams toward balanced, high-performance architectures.

TYMIQ’s five pillars of a reliable cloud architecture framework

Addressing key modernization challenges

Moving to the cloud isn’t simply a matter of “lifting and shifting” pipelines. Most enterprises have accumulated years – sometimes decades – of business logic, workflow rules, and execution patterns baked into their systems.

Whether modernization is manual, semi-automated, or fully automated, teams face four major data integration challenges: aligning with cloud-native data warehouse constructs, converting complex logic safely, meeting performance SLAs, and surfacing hidden technical debt.

Below is a streamlined breakdown of the most common roadblocks – and our practice-based advice on how to avoid them.

1. Adapting to cloud data warehouse semantics

Cloud platforms introduce fundamentally different storage formats, data types, partitioning strategies, and optimization rules. Mapping legacy schemas to these new paradigms is rarely straightforward – and rarely one-to-one.

Cloud warehouses and lakehouses each have distinct conventions:

- BigQuery relies on STRING types, REPEATED arrays, and RECORD objects.

- Snowflake supports semi-structured types like OBJECT, VARIANT, and ARRAY.

- Redshift mirrors PostgreSQL types but lacks native LOB support.

- Teradata workloads often rely on CLOB/BLOB, requiring workarounds such as storing objects in S3 and keeping references in the warehouse.

This means schema conversion is not just a pipeline configuration task – you should understand the native behaviors of the target engine and adapt data models to optimize cost, performance, and BI accessibility.

Common compatibility gaps:

- Incorrect or lossy data type mappings

- Legacy assumptions around indexes, constraints, and partitions

- ETL-native functions or libraries that lack cloud equivalents

- Misalignment between the source schema design and modern cloud-optimal modeling

A cloud-native mindset is essential: when direct equivalents don't exist, custom transformations or architectural pivots are required.

2. Converting complex legacy logic safely

Manual or semi-automated conversion introduces risk and slows down any software modernization. But automation without the right guardrails can be equally problematic – especially when legacy ETL logic is deeply embedded in proprietary constructs.

Large Informatica, DataStage, or Ab Initio workloads often contain:

- 10k+ lines of script per workflow

- Running aggregates, dynamic lookups, and link conditions

- Parameterized or dynamically generated queries

- Assignment variables, sequences, or command tasks

- Custom error handling, orchestration logic, and conditional flows

Migrating this requires more than SQL translation. It demands understanding the intent behind each mapping and reconstructing it in a distributed, cloud-native execution environment.

Common compatibility gaps:

- Partial or missing documentation

- Automated tools misinterpret complex expressions

- Legacy functions needing UDF rewrites

- Logic spread across events, workflows, scripts, and parameters that must be re-stitched coherently

- ETL flows tightly coupled to the warehouse, including logic that writes back into OLAP systems for BI workflows

Cloud-native transformation demands a structured approach: hierarchical workflow representation, logic decomposition, mapping parallelism, and a reliable translation of both SQL and orchestration semantics.

3. Meeting performance SLAs in the target environment

Even after a successful functional migration, performance gaps are common. What runs efficiently in a monolithic MPP system may behave very differently in a disaggregated cloud microservices architecture.

Therefore, cloud systems vary widely in their support for advanced SQL and procedural logic. For example:

- Many platforms lack robust stored procedure support.

- Recursive queries, PL/SQL-style cursors, triggers, and nested dependencies often require re-engineering.

- Platforms like EMR, Dataproc, and HDInsight require custom implementations for orchestration patterns previously handled inside the warehouse.

Common compatibility gaps:

- Logic that doesn’t translate efficiently into a distributed compute engine

- Stored procedures replaced with orchestration layers (Airflow, Argo, Step Functions, etc.)

- Over-reliance on cluster scaling as a “fix,” which only inflates cost

- Workloads that are technically correct but resource-inefficient or unable to meet production SLAs

To meet SLAs, optimization should happen in two layers:

- Workload optimization (query patterns, data model adjustments, decomposing legacy procedural logic)

- Infrastructure optimization (autoscaling policies, storage formats, compute sizing)

4. Exposing and reducing technical debt

Years of incremental patches and quick fixes create technical debt that becomes painfully visible during migration. Modernizing ETL is an opportunity to surface, evaluate, and reduce this debt before it propagates into the new platform.

Technical debt exists across multiple layers:

- Schema: partitioning, clustering/bucketing strategy, distribution keys, sort policies

- Data: formats, compression, sparsity, and historical inconsistencies

- Code: interdependencies, anti-patterns, resource-intensive logic

- Architecture: ingestion → processing → BI models and their cross-domain dependencies

- Execution: orchestrated job dependencies and parallelization limits

Common compatibility gaps:

- Poor visibility into job lineage

- Hard-to-detect interdependencies across shell scripts, ETL workflows, stored procedures, and scheduler tasks

- Scripts that seem independent but break under parallel execution

Legacy patterns that undermine cloud elasticity, such as serialized transformations or heavyweight monolithic jobs

An intelligent assessment layer is essential since strong API integration helps reduce hidden dependencies and simplifies maintenance across systems. It should provide full lineage for technical debt management, identify performance anti-patterns, highlight refactoring opportunities, and prescribe cloud-native architectural alternatives.

To learn more about reducing technical debt in ETL systems, check out our dedicated material.

What to do next

Pilot using one pipeline with representative scale and complexity. Implement two parallel paths: serverless ingestion/validation and warehouse ELT transformations. Measure cost, latency, and operational overhead. Use the cost considerations to evaluate workload shape and determine if serverless or dedicated compute provides better long-term characteristics.

Even after transformation, workloads must be validated against live datasets to:

- confirm functional equivalence

- verify end-to-end interdependencies

- ensure performance meets target-state SLAs

- certify readiness for production execution cycles

Cloud modernization isn’t finished until these validation loops are complete.

When you take this measured, data-driven approach, you don’t just modernize pipelines – you build a future-ready architecture that scales with your business. Bit by bit, you replace bottlenecks with momentum and turn technical debt into a strategic advantage.

.webp)

.svg)